My intent is to drink about 6 tablespoons (not the measuring kind, but the silverware kind) of sugar mixed with water during the day every day. Then at night when I get home after work, I'm supposed to drink 2 tablespoons of extra-light olive oil (ELOO) with water before I eat anything. I've got the sugar water part down. But when I get home, I dig into the food right away.

The thing is ... I'm not even that hungry. I just eat out of boredom. I'd like to not even go into the kitchen and instead go into the office and play on the computer, but that is not an option because I cannot leave my dear wife to tend to 4 hungry kids while I'm off playing games on the computer.

So I'm thinking out loud here ... maybe I can try drinking a large cup of Crystal Light again when I get home ... put lots of ice in it so I can chew on ice ... maybe that'll satisfy my need to masticate.

Other than that, the Shangri-la diet is going well. I'm still hovering right under 210 despite eating Church's Chicken, potato salad, ice cream, brownies and pretty much anything else laying around the house this weekend. I thought I'd be back up to 215 on Monday morning, but the scale went right up to just under 210.

I figure if I can "be good" during the week, I can then go on an 1 to 2 hour workout Saturday morning and then "relax" the rest of the weekend.

One other thing to write ... just a few days before I hopped back onto the diet, I discovered a song by The White Stripes entitled Sugar Never Tasted So Good. It's a catchy song like most White Stripes songs. I kept chuckling the first time I heard it which was the day after I started Shangri-la again.

Tuesday, October 27, 2009

Saturday, October 24, 2009

Carnage and Culture: Landmark Battles in the Rise of Western Power by Victor Davis Hanson

What a tremendous book! I read this book in the Fall of 2009. I was so impressed and fascinated by this book I decided to read it again. This is one of those books that should be required reading for every Western Civilization citizen from Europe to America.

As I've finished each chapter, I updated this post with quotes and thoughts I found interesting.

Never has a book taught me as much about my Western culture heritage as this book has. The sampling of battles across time and space gave me an nice overview of Western civilization. After reading this book, I wished I could take the History of Civilization courses at BYU again. I also realized how little history I know and how interesting history can be. There's still so many books to read with so little time ...

Salamis, September 28, 480 B.C.

The first battle discussed is Salamis. The main point of this chapter was that free men fight better than enslaved men. The Greek concept called eleutheria was why the Greeks defeated the Persians in this decisive battle.

Here are a few quotes I particularly liked:

"Greek moralists, in relating culture and ethics, had long equated Hellenic poverty with liberty and excellence, Eastern affluence with slavery and decadence. So the poet Phycylides wrote, 'The law-biding polis, though small and set on a high rock, outranks senseless Ninevah'" (p. 33).

"When asked why the Greeks did not come to terms with Persia at the outset, the Spartan envoys tell Hydarnes, the military commander of the Western provinces, that the reason is freedom: 'Hydarnes, the advice you give us does not arise from a full knowledge of our situation. You are knowledgeable about only one half of what is involved; the other half is blank to you. The reason is that you understand well enough what slavery is, but freedom you have never experienced, so you do not know if it tastes sweet or not. If you ever did come to experience it, you would advise us to fight for it not with spears only, but with axes too.'" (p. 47).

So the first element of why Western culture is so deadly is that we fight for freedom ... we fight for our families and our way of life. I wonder if many of our citizens today realize what we have. If we were to taste or experience anything less than the freedom we have, would we then be more willing to fight for it? Sometimes I feel that too many take freedom for granted.

Guagamela, October 1, 331 B.C.

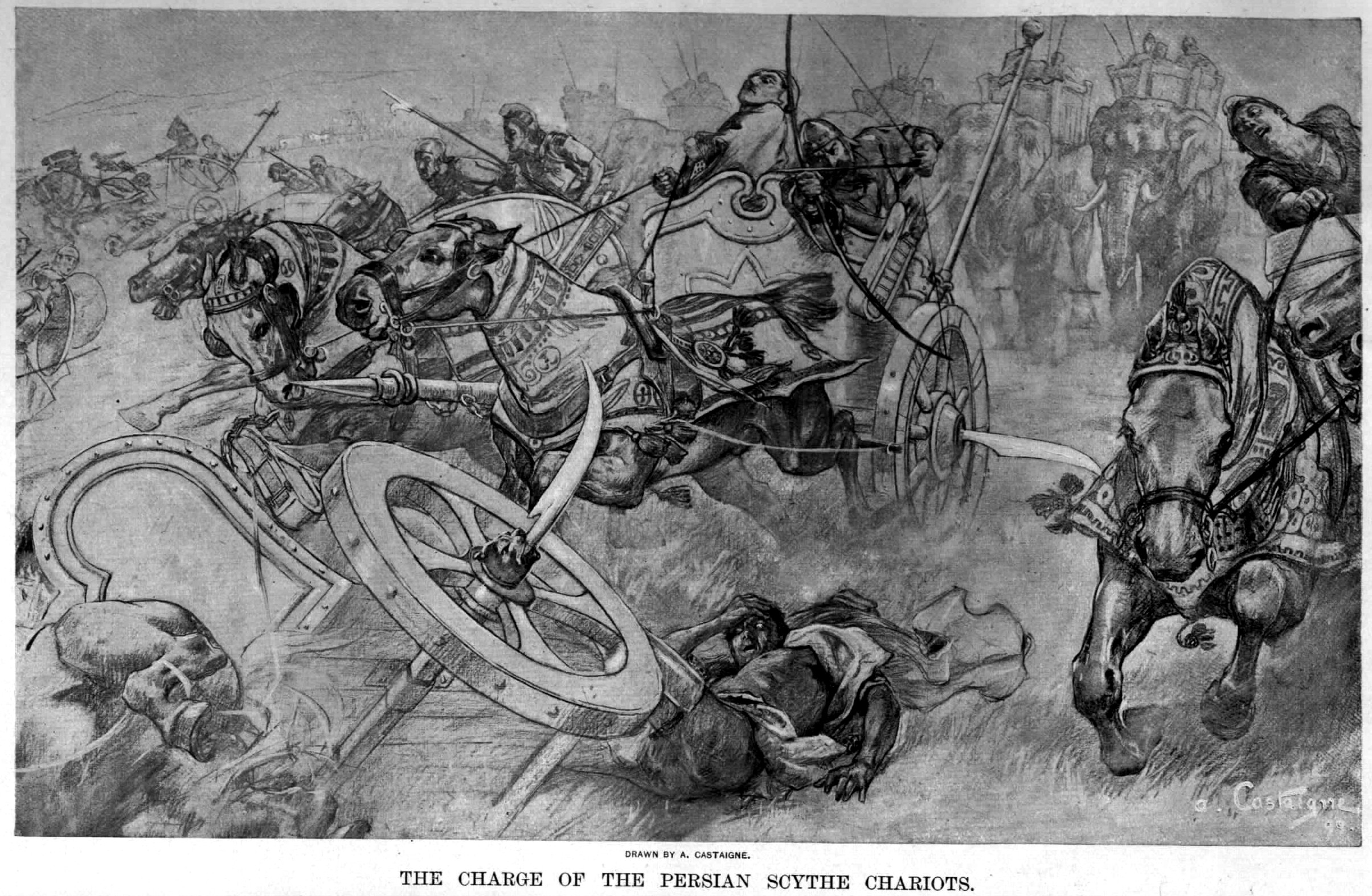

The second battle discussed is Guagamela fought by Alexander the Great. What the Macedonians gave Western culture was shock battle. Despite the perfect, prepped and flat terrain for his scythed chariots, Darius was not fully prepared for the full-on onslaught of Alexander's shock troops.

"Alexander won at Guagamela and elsewhere in Asia for the same reasons Greek infantry won overseas: theirs was a culture of face-to-face battle of rank-and-file columns, not a contest of mobility, numerical superiority, or ambush." (p. 70)

"Philip (Alexander's father) brought Western warefare an enhanced notion of decisive war ... The Macedonians saw no reason to stop fighting at the collapse of their enemy on the battlefield when he could be demolished in toto, and his house and land looted, destroyed, or annexed." (p. 77)

"Alexander brilliantly employed decisive battle in terrifying ways that its long-conquered Hellenic inventors had never imagined - and in a stroke of real genius he proclaimed that he had killed for the idea of brotherly love. To Alexander the strategy of war meant not the defeat of the enemy, the return of the dead, the construction of a trophy, and the settlement of existing disputes, but, as his father had taught him, the annihilation of all combatants and the destruction of the culture itself that had dared to field such opposition to his imperial rule." (p. 83)

"I leave the reader with the dilemma of the modern age: the Western manner of fighting bequeathed to us from the Greeks and enhanced by Alexander is so destructive and so lethal that we have essentially reached an impasse. Few non-Westerners wish to meet our armies in battle. The only successful response to encountering a Western army seems to be to marshal another Western army. The state of technology and escalation is such that any intra-Western conflict would have the opposite result of its original Hellenic intent: abject slaughter on both sides would result, rather than quick resolution. Whereas the polis Greeks discovered shock battle as a glorious method of saving lives and confining conflict to an hour's worth of heroics between armored infantry, Alexander the Great and the Europeans who followed sought to unleash the entire power of their culture to destroy their enemies in a horrendous moment of shock battle. That moment is now what haunts us" (p. 98)

Cannae, August 2, 216 B.C.

Hannibal Barca was brilliant, but the Roman way of war was truly resilient. After it's second greatest defeat ever, Rome did not wallow in the mire of loss. Rather it came back with avengence. By 202 B.C. the Romans had turned the war around and had invaded Carthage. The Battle of Zama brought the utter defeat of Carthage. The reason Rome was able to turn defeat in Cannae into complete victory was due to their constitution and their nation-state, both of which enabled it to systematically raise, organize and deploy legions year after year, battle after battle and war after war.

"Hannibal's pleasure in his victory in the battle was not so great as his dejection, once he saw with amazement how steady and great-souled were the Romans in their deliberations." (Polybius, p. 111)

"The irony of the Second Punic War was that Hannibal, the sworn enemy of Rome, did much to make Rome's social and military foundations even stronger by incorporating the once 'outsider' into the Roman commonwealth. By his invasion, he helped accelerate a second evolution in the history of Western republican government that would go well beyond the parochial constitutions of the Greek city-states. The creation of a true nation-state would have military ramifications that would shake the entire Mediterranean world to its core - and help explain much of the frightening military dynamism of the West today." (p. 121)

"Under the late republic and empire to follow, freed slaves and non-Italian Mediterranean peoples would find themselves nearly as equal under the law as Roman blue bloods.

"This revolutionary idea of Western citizenship - replete with ever more rights and responsibilities - would provide superb manpower for the growing legions and a legal framework that would guarantee that the men who fought felt that they themselves in a formal and contractual sense had ratified the conditions of their own battle services. The ancient Western world would soon come to define itself by culture rather than by race, skin color, or language." (p. 122)

"For although the Romans had clearly been defeated in the field, and their reputation in arms ruined, yet because of the singularity of their constitution, and by wisdom of their deliberative counsel, they not only reclaimed the sovereignty of Italy, and went on to conquer the Carthaginians, but in just a few years themselves became rulers of the entire world." (Polybius, p. 132)

Poitiers, October 11, 732

The Battle of Poitiers or Battle of Tours does not have a lot of accurate information on it. There are so many differing sources as well as differing opinions on the battle, that it is hard to discern truth from speculation. Hanson readily admits this, but it is all beside the point. The important points are 1) Charles Martel led the European army with infantry (without horses) and 2) the Battle of Poitiers was key in the rise of Western European power.

There are several parts I highlighted in the book, but I am only going to mention one because I think it properly sums up the point of this chapter.

"Europe's renewed strength against the Other in the age of gunpowder was facilitated by the gold of the New World, the mass employment of firearms, and new designs of military architecture. Yet the proper task of the historian is not simply to chart the course for this amazing upsurge in European influence, but to ask why the "Military Revolution" took place in Europe and not elsewhere. The answer is that throughout the Dark and Middle Ages, European military traditions founded in classical antiquity were kept alive and improved upon in a variety of bloody wars against Islamic armies, Viking raiders, Mongols, and northern barbarian tribes. The main components of the Western military tradition of freedom, decisive battle, civic militarism, rationalism, vibrant markets, discipline, disent, and free critique were not wiped out by the fall of Rome. Instead they formed the basis of a succession of Merovingian, Carolingian, French, Dutch, Swiss, German, English, and Spanish militaries that continued the military tradition of classical antiquity.

"Key to this indefatigability was the ancient and medieval emphasis on foot soldiers, and especially the idea of free property owners, rather than slaves or serfs, serving as heavily armed infantrymen." (p. 168)

Tenochtitlán, June 24, 1520 - August 13, 1521

The title of this chapter is named "Technology and the Wages of Reason." It is so named because he argues that Western culture cultivated an environment of scientific research which was responsible for why a small group of conquistadors destroyed an entire civilization.

I have to admit that this chapter was the most fascinating of all the chapters in this book. After reading about La Noche Triste and how Cortés barely escaped the Aztec capitol and then in less than a year how he and his men annihilated the Aztecs, I was truly in awe. Taking all morality about the conquistadors out of the equation, Cortés' comeback has to be one of the all-time best comebacks. And he was able to make that comeback because of the culture in which he was raised and lived.

"Under the tenets of European wars of annihilation, letting a man like Cortés - or an Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar, Richard the Lion-Hearted, Napolean, or Lord Chelmsford - escape with his army after defeat was no victory, but only an assurance that the next round would be bloodier still, when an angrier, more experienced, and wiser force would return to settle the issue once and for all." (p. 181)

"In the case of all discoveries, the results of previous labors that have been handed down from others have been advanced bit by bit by those who have taken them on." (Aristotle p. 231)

"Western technological superiority is not merely a result of the military renaissance of the sixteenth century or an accident of history, much less the result of natural resources, but predicated on an age-old method of investigation, a peculiar mentality that dates back to the Greeks and not earlier." (p. 231)

"Cortés, like Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar, Don Juan of Austria, and other Western captains, often annihilated without mercy their numerically superior foes, not because their own soldiers were necessarily better in war, but because their traditions of free inquiry, rationalism, and science most surely were." (p. 232)

Lepanto, Ocotber 7, 1571

The purpose of this chapter ("The Market-or Capitalism Kills") is to offer evidence of how Western technology and capitalism defeat non-Western culture. Throughout history, non-Western cultures sought out Westerners for technology because non-Western cultures never developed a natural inquiry into science and capitalism.

At Lepanto, it was the free market which allowed the money to be raised to invest in quality and powerful ships which, in the first few minutes of the battle, decimated many of the Turkish ships.

"In Europe the social ramifications of military technology were far less important that its simple efficacy; the sultan, however, was careful that weapons in and of themselves - like printing presses - should not prove to be sources of social and cultural unrest." (p. 248)

Regarding the aftermath of the battle, "there was to be little exegesis and analysis concerning the shortcomings in the sultan's equipment, command, and naval organization.

"In contrast, dozens of highly emotive firsthand narratives in Italian and Spanish - often at odds with each other in a factual and analytical sense - spread throughout the Mediterranean." (p. 251)

"Before the fleet had even sailed, papal ministers had calculated the entire cost of manning two hundred galleys, with crews and provisions, for a year - and had raised the necessary funds in advance." (p. 258)

"The sultan sought out European traders, ship designers, seamen, and imported firearms - even portrait painters - while almost no Turks found their services required in Europe." (p. 262)

And lastly, on a more contemporary note, I found this quote quite appropriate for these times in 2010: "In the twilight of the empire, observers were quick to point out that Roman military impotence was a result of a debased currency, exorbitant taxation, and the manipulation of the market by inefficient government price controls, corrupt governmental traders, and unchecked tax farmers - the wonderful system of raising capital operating in reverse as it devoured savings and emptied the countryside of once-productive yeomen." (p. 275)

Rorke's Drift, January 22-23, 1879

The main point of this chapter was to demonstrate discipline - the ability to do as commanded in order to fight as one group - to defend the group instead of seeking glory for the individual warrior.

The main point of this chapter was to demonstrate discipline - the ability to do as commanded in order to fight as one group - to defend the group instead of seeking glory for the individual warrior.

There are two quotes that sum up this chapter quite well.

"The Europeans were willing to fight 365 days a year, day or night, regardless of the exigencies of either their Christian faith or the natural year. Bad weather, disease, and difficult geography were seen as simple obstacles to be conquered by the appropriate technology, military discipline, and capital, rarely as expressions of divine ill will or the hostility of all-powerful spirits. Europeans often looked at temporary setbacks differently from their adversaries in Asia, America, or Africa. Defeat signaled no angry god or adverse fate, but rather a rational flaw in either tactics, logistics, or technology, one to be easily remedied on the next occasion - through careful audit and analysis. The British in Zululand, like all Western armies, and as Clausewitz saw, did envision battle as a continuation of politics by other means. Unlike the Zulus, the British army did not see war largely as an occasion for individual warriors to garner booty, women, or prestige." (p. 309)

"We hear through Greek literature of the necessity of staying in rank, of rote and discipline as more important than mere strength and bravado. Men carry their shields, Plutarch wrote, 'for the sake of the entire line' (Moralis 220A). Real strength and bravery were for carrying a shield in formation, not for killing dozens of the enmy in iindividual combat, which was properly the stuff of epic and mythology. Xenophon remind us that from freeholding property owners comes such group cohesion and discipline: 'In fighting, just as in working the soil, it is necessary to have the help of other people.' (Oeconomicus 5.14) Punishments were given only to those who threw down their shields, broke rank, or caused panic, never to those who failed to kill enough of the enemy." (p. 326)

"In the long annals of military history, it is difficult to find anything quite like Rorke's Drift, where a beleaguered force, outnumbered forty to one, survived and killed twenty men for every defender lost. But then it is also rare to find warriors as well trained as European soldiers, and rarer still to find any Europeans as disciplined as the British redcoats of the late nineteenth century." (p. 333)

Battle of Midway, June 4-8, 1942

The Battle of Midway is used to demonstrate Western individualism. Hanson cites four critical ways the Americans demonstrated Western individualism and thus won this key battle.

1) "the breaking of the Japanese naval codes"

2) "the repair of the carrier Yorktown"

3) "the nature of the U.S. naval command"

4) "the behavior of American pilots" (p. 370)

He also notes that Japan, although militarily "Westernized" did not change culturally in conjunction with their military revolution and thus caused failures in their defeat at Miday.

Here are a few quotes I had noted from the book.

"Yet the Japanese wide-scale adoption of Western technology was also not always what it seemed at first glance. There remained stubborn Japanese cultural traditions that would resurface to hamper a truly unblinkered Western approach to scientific research and weapons development. The Japanese had always entertained an ambiguous attitude about their own breakneck efforts at Westernization." (p. 359)

"The Japanese were not comfortable with the rather different Western notion of seeking out the enemy without deception, to engage in bitter shock collision, one whose deadliness would prove decisive for the side with the greater firepower, discipline, and numbers." (p. 363)

"Although slow to anger, Western constitutional governments usually preferred wars of annihilation ... all part of a cultural tradition to end hostilities quickly, decisively, and utterly." (p. 364-5)

"In the final analysis, the root cause of Japan's defeat, not alone in the Battle of Midway but in the entire war, lies deep in the Japanese national character. There is an irrationality and impulsiveness about our people which results in actions that are haphazard and often contradictory. A tradition of provincialism makes us narrow-minded and dogmatic, reluctant to discard prejudices and slow to adopt even necessary improvements if they require a new concept. Indecisive and vacillating, we succomb readily to conceit, which in turn makes us disdainful of others. Opportunistic but lacking in a spirit of daring and independance, we are wont to place reliance on others and to truckle to superiors." (M. Fuchida and M. Okumiya, Midway, the Battle That Doomed Japan, 247). (p. 370)

Tet, January 31-April 6, 1968

Reading this chapter, like the rest of the book, was quite enlightening. This chapter did much to explain not only this key battle in the Vietnam War, but also why and how that war was fought. All I've known of this war is from watching Hollywood movies. So reading this chapter has really opened my eyes.

Like the chapter on Cortes and the Aztecs, in which I learned some heavy statistics about the gory and bloody habits of the Aztecs, I learned about the brutality of the North Vietnamese. It seems that when it comes to Conquistadores and the US military in Vietnam, all we hear about are the brutalities of Cortes and the Marines. But when compared to the Aztecs and North Vietnamese, these sins seem to pale in comparison. The Western media was quick to point out Western mistakes and atrocities, but mute on the utter evil the Communists committed. The reasons behind this imbalanced view are complex, but the fact that this dissention even exists is wholly attributable to Western culture.

There are two passages that stood out to me. The first essentially discusses what went wrong in the war. The second sums up the role of dissent and self-critique, which was always on display, in the Viet Nam war.

"How odd that at the pinnacle of a lethal 2,500-year-old military tradition, American planners completely ignored the tenets of the entire Western military heritage. Cortes - also outnumbered, far from home, in a strange climate, faced with near insurrection among his own troops and threats of recall from home, fighting a fanatical enemy that gave no quarter, with fickle allies - at least knew that his own soldiers and the Spanish crown cared little how many actual bodies of the enemy he might count, but a great deal whether he took and held Tenochtitlan and so ended resistance with his army largely alive. Lord Chelmsford - likewise surrounded by criticism in and out of the army, under threat of dismissal, ignorant of the exact size, nature, and location of his enemy, suspicious of Boer colonialists, English idealists, and tribal allies - at least realized that until he overran Zululand, destroyed the nucleus of the royal kraals, and captured the king, the war would go on despite the thousands of Zulus who fell to his deadly Martini-Hentry rifles.

"American generals never fully grasped, or never successfully transmitted to the political leadership in Washington, that simple lesson: that the number of enemy killed meant little in and of itself if the land of South Vietnam was not secured and held and the antagonist North Vietnam not invaded, humiliated, or rendered impotent. Few, if any, of the top American brass resigned out of principle over the disastrous rules of engagement that ensured their brave soldiers would be killed without a real chance of decisive military victory. It was as if thousands of graduates from American's top military academies had not a clue about their own lethal heritage of the Western way of war." (p. 407)

"This strange propensity for self-critique, civilian audit, and popular criticism of military operations - itself part of the larger Western tradition of personal freedom, consensual government, and individualism - thus poses a paradox. The encouragement of open assessment and the acknowledgment of error within the military eventually bring forth superior planning and a more flexible response to adversity.

"At the same time, this freedom to distort can often hamper military operations of the moment." (p. 438)

Summary

I'm afraid I'm a victim to how Western media has continually criminalized the West for its wars and brutalities. There are two sides to every story. It seems as though all we hear is the one-sided, constant put-down by those who want to see the West destroyed. The way I see it is that if it were not for the West and its culture, the world would be a much more brutal place with much more death and destruction and injustice. Death and destruction and injustice will always exist among our imperfect human race. But that does not mean we simply let tyrants rule us or that we impugn those who seek to destroy tyranny. The West has consistently provided a culture which allows freedom to exist and flourish. Without that culture (and the military tradition to go with it), the world would indeed be ruled by tyrants and millions more would be slaves rather than free men.

As I've finished each chapter, I updated this post with quotes and thoughts I found interesting.

Never has a book taught me as much about my Western culture heritage as this book has. The sampling of battles across time and space gave me an nice overview of Western civilization. After reading this book, I wished I could take the History of Civilization courses at BYU again. I also realized how little history I know and how interesting history can be. There's still so many books to read with so little time ...

Salamis, September 28, 480 B.C.

Here are a few quotes I particularly liked:

"Greek moralists, in relating culture and ethics, had long equated Hellenic poverty with liberty and excellence, Eastern affluence with slavery and decadence. So the poet Phycylides wrote, 'The law-biding polis, though small and set on a high rock, outranks senseless Ninevah'" (p. 33).

"When asked why the Greeks did not come to terms with Persia at the outset, the Spartan envoys tell Hydarnes, the military commander of the Western provinces, that the reason is freedom: 'Hydarnes, the advice you give us does not arise from a full knowledge of our situation. You are knowledgeable about only one half of what is involved; the other half is blank to you. The reason is that you understand well enough what slavery is, but freedom you have never experienced, so you do not know if it tastes sweet or not. If you ever did come to experience it, you would advise us to fight for it not with spears only, but with axes too.'" (p. 47).

So the first element of why Western culture is so deadly is that we fight for freedom ... we fight for our families and our way of life. I wonder if many of our citizens today realize what we have. If we were to taste or experience anything less than the freedom we have, would we then be more willing to fight for it? Sometimes I feel that too many take freedom for granted.

Guagamela, October 1, 331 B.C.

The second battle discussed is Guagamela fought by Alexander the Great. What the Macedonians gave Western culture was shock battle. Despite the perfect, prepped and flat terrain for his scythed chariots, Darius was not fully prepared for the full-on onslaught of Alexander's shock troops.

"Alexander won at Guagamela and elsewhere in Asia for the same reasons Greek infantry won overseas: theirs was a culture of face-to-face battle of rank-and-file columns, not a contest of mobility, numerical superiority, or ambush." (p. 70)

"Philip (Alexander's father) brought Western warefare an enhanced notion of decisive war ... The Macedonians saw no reason to stop fighting at the collapse of their enemy on the battlefield when he could be demolished in toto, and his house and land looted, destroyed, or annexed." (p. 77)

"Alexander brilliantly employed decisive battle in terrifying ways that its long-conquered Hellenic inventors had never imagined - and in a stroke of real genius he proclaimed that he had killed for the idea of brotherly love. To Alexander the strategy of war meant not the defeat of the enemy, the return of the dead, the construction of a trophy, and the settlement of existing disputes, but, as his father had taught him, the annihilation of all combatants and the destruction of the culture itself that had dared to field such opposition to his imperial rule." (p. 83)

"I leave the reader with the dilemma of the modern age: the Western manner of fighting bequeathed to us from the Greeks and enhanced by Alexander is so destructive and so lethal that we have essentially reached an impasse. Few non-Westerners wish to meet our armies in battle. The only successful response to encountering a Western army seems to be to marshal another Western army. The state of technology and escalation is such that any intra-Western conflict would have the opposite result of its original Hellenic intent: abject slaughter on both sides would result, rather than quick resolution. Whereas the polis Greeks discovered shock battle as a glorious method of saving lives and confining conflict to an hour's worth of heroics between armored infantry, Alexander the Great and the Europeans who followed sought to unleash the entire power of their culture to destroy their enemies in a horrendous moment of shock battle. That moment is now what haunts us" (p. 98)

Cannae, August 2, 216 B.C.

Hannibal Barca was brilliant, but the Roman way of war was truly resilient. After it's second greatest defeat ever, Rome did not wallow in the mire of loss. Rather it came back with avengence. By 202 B.C. the Romans had turned the war around and had invaded Carthage. The Battle of Zama brought the utter defeat of Carthage. The reason Rome was able to turn defeat in Cannae into complete victory was due to their constitution and their nation-state, both of which enabled it to systematically raise, organize and deploy legions year after year, battle after battle and war after war.

"Hannibal's pleasure in his victory in the battle was not so great as his dejection, once he saw with amazement how steady and great-souled were the Romans in their deliberations." (Polybius, p. 111)

"The irony of the Second Punic War was that Hannibal, the sworn enemy of Rome, did much to make Rome's social and military foundations even stronger by incorporating the once 'outsider' into the Roman commonwealth. By his invasion, he helped accelerate a second evolution in the history of Western republican government that would go well beyond the parochial constitutions of the Greek city-states. The creation of a true nation-state would have military ramifications that would shake the entire Mediterranean world to its core - and help explain much of the frightening military dynamism of the West today." (p. 121)

"Under the late republic and empire to follow, freed slaves and non-Italian Mediterranean peoples would find themselves nearly as equal under the law as Roman blue bloods.

"This revolutionary idea of Western citizenship - replete with ever more rights and responsibilities - would provide superb manpower for the growing legions and a legal framework that would guarantee that the men who fought felt that they themselves in a formal and contractual sense had ratified the conditions of their own battle services. The ancient Western world would soon come to define itself by culture rather than by race, skin color, or language." (p. 122)

"For although the Romans had clearly been defeated in the field, and their reputation in arms ruined, yet because of the singularity of their constitution, and by wisdom of their deliberative counsel, they not only reclaimed the sovereignty of Italy, and went on to conquer the Carthaginians, but in just a few years themselves became rulers of the entire world." (Polybius, p. 132)

Poitiers, October 11, 732

The Battle of Poitiers or Battle of Tours does not have a lot of accurate information on it. There are so many differing sources as well as differing opinions on the battle, that it is hard to discern truth from speculation. Hanson readily admits this, but it is all beside the point. The important points are 1) Charles Martel led the European army with infantry (without horses) and 2) the Battle of Poitiers was key in the rise of Western European power.

There are several parts I highlighted in the book, but I am only going to mention one because I think it properly sums up the point of this chapter.

"Europe's renewed strength against the Other in the age of gunpowder was facilitated by the gold of the New World, the mass employment of firearms, and new designs of military architecture. Yet the proper task of the historian is not simply to chart the course for this amazing upsurge in European influence, but to ask why the "Military Revolution" took place in Europe and not elsewhere. The answer is that throughout the Dark and Middle Ages, European military traditions founded in classical antiquity were kept alive and improved upon in a variety of bloody wars against Islamic armies, Viking raiders, Mongols, and northern barbarian tribes. The main components of the Western military tradition of freedom, decisive battle, civic militarism, rationalism, vibrant markets, discipline, disent, and free critique were not wiped out by the fall of Rome. Instead they formed the basis of a succession of Merovingian, Carolingian, French, Dutch, Swiss, German, English, and Spanish militaries that continued the military tradition of classical antiquity.

"Key to this indefatigability was the ancient and medieval emphasis on foot soldiers, and especially the idea of free property owners, rather than slaves or serfs, serving as heavily armed infantrymen." (p. 168)

Tenochtitlán, June 24, 1520 - August 13, 1521

The title of this chapter is named "Technology and the Wages of Reason." It is so named because he argues that Western culture cultivated an environment of scientific research which was responsible for why a small group of conquistadors destroyed an entire civilization.

I have to admit that this chapter was the most fascinating of all the chapters in this book. After reading about La Noche Triste and how Cortés barely escaped the Aztec capitol and then in less than a year how he and his men annihilated the Aztecs, I was truly in awe. Taking all morality about the conquistadors out of the equation, Cortés' comeback has to be one of the all-time best comebacks. And he was able to make that comeback because of the culture in which he was raised and lived.

"Under the tenets of European wars of annihilation, letting a man like Cortés - or an Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar, Richard the Lion-Hearted, Napolean, or Lord Chelmsford - escape with his army after defeat was no victory, but only an assurance that the next round would be bloodier still, when an angrier, more experienced, and wiser force would return to settle the issue once and for all." (p. 181)

"In the case of all discoveries, the results of previous labors that have been handed down from others have been advanced bit by bit by those who have taken them on." (Aristotle p. 231)

"Western technological superiority is not merely a result of the military renaissance of the sixteenth century or an accident of history, much less the result of natural resources, but predicated on an age-old method of investigation, a peculiar mentality that dates back to the Greeks and not earlier." (p. 231)

"Cortés, like Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar, Don Juan of Austria, and other Western captains, often annihilated without mercy their numerically superior foes, not because their own soldiers were necessarily better in war, but because their traditions of free inquiry, rationalism, and science most surely were." (p. 232)

Lepanto, Ocotber 7, 1571

The purpose of this chapter ("The Market-or Capitalism Kills") is to offer evidence of how Western technology and capitalism defeat non-Western culture. Throughout history, non-Western cultures sought out Westerners for technology because non-Western cultures never developed a natural inquiry into science and capitalism.

At Lepanto, it was the free market which allowed the money to be raised to invest in quality and powerful ships which, in the first few minutes of the battle, decimated many of the Turkish ships.

"In Europe the social ramifications of military technology were far less important that its simple efficacy; the sultan, however, was careful that weapons in and of themselves - like printing presses - should not prove to be sources of social and cultural unrest." (p. 248)

Regarding the aftermath of the battle, "there was to be little exegesis and analysis concerning the shortcomings in the sultan's equipment, command, and naval organization.

"In contrast, dozens of highly emotive firsthand narratives in Italian and Spanish - often at odds with each other in a factual and analytical sense - spread throughout the Mediterranean." (p. 251)

"Before the fleet had even sailed, papal ministers had calculated the entire cost of manning two hundred galleys, with crews and provisions, for a year - and had raised the necessary funds in advance." (p. 258)

"The sultan sought out European traders, ship designers, seamen, and imported firearms - even portrait painters - while almost no Turks found their services required in Europe." (p. 262)

And lastly, on a more contemporary note, I found this quote quite appropriate for these times in 2010: "In the twilight of the empire, observers were quick to point out that Roman military impotence was a result of a debased currency, exorbitant taxation, and the manipulation of the market by inefficient government price controls, corrupt governmental traders, and unchecked tax farmers - the wonderful system of raising capital operating in reverse as it devoured savings and emptied the countryside of once-productive yeomen." (p. 275)

Rorke's Drift, January 22-23, 1879

The main point of this chapter was to demonstrate discipline - the ability to do as commanded in order to fight as one group - to defend the group instead of seeking glory for the individual warrior.

The main point of this chapter was to demonstrate discipline - the ability to do as commanded in order to fight as one group - to defend the group instead of seeking glory for the individual warrior.There are two quotes that sum up this chapter quite well.

"The Europeans were willing to fight 365 days a year, day or night, regardless of the exigencies of either their Christian faith or the natural year. Bad weather, disease, and difficult geography were seen as simple obstacles to be conquered by the appropriate technology, military discipline, and capital, rarely as expressions of divine ill will or the hostility of all-powerful spirits. Europeans often looked at temporary setbacks differently from their adversaries in Asia, America, or Africa. Defeat signaled no angry god or adverse fate, but rather a rational flaw in either tactics, logistics, or technology, one to be easily remedied on the next occasion - through careful audit and analysis. The British in Zululand, like all Western armies, and as Clausewitz saw, did envision battle as a continuation of politics by other means. Unlike the Zulus, the British army did not see war largely as an occasion for individual warriors to garner booty, women, or prestige." (p. 309)

"We hear through Greek literature of the necessity of staying in rank, of rote and discipline as more important than mere strength and bravado. Men carry their shields, Plutarch wrote, 'for the sake of the entire line' (Moralis 220A). Real strength and bravery were for carrying a shield in formation, not for killing dozens of the enmy in iindividual combat, which was properly the stuff of epic and mythology. Xenophon remind us that from freeholding property owners comes such group cohesion and discipline: 'In fighting, just as in working the soil, it is necessary to have the help of other people.' (Oeconomicus 5.14) Punishments were given only to those who threw down their shields, broke rank, or caused panic, never to those who failed to kill enough of the enemy." (p. 326)

"In the long annals of military history, it is difficult to find anything quite like Rorke's Drift, where a beleaguered force, outnumbered forty to one, survived and killed twenty men for every defender lost. But then it is also rare to find warriors as well trained as European soldiers, and rarer still to find any Europeans as disciplined as the British redcoats of the late nineteenth century." (p. 333)

Battle of Midway, June 4-8, 1942

The Battle of Midway is used to demonstrate Western individualism. Hanson cites four critical ways the Americans demonstrated Western individualism and thus won this key battle.

1) "the breaking of the Japanese naval codes"

2) "the repair of the carrier Yorktown"

3) "the nature of the U.S. naval command"

4) "the behavior of American pilots" (p. 370)

He also notes that Japan, although militarily "Westernized" did not change culturally in conjunction with their military revolution and thus caused failures in their defeat at Miday.

Here are a few quotes I had noted from the book.

"Yet the Japanese wide-scale adoption of Western technology was also not always what it seemed at first glance. There remained stubborn Japanese cultural traditions that would resurface to hamper a truly unblinkered Western approach to scientific research and weapons development. The Japanese had always entertained an ambiguous attitude about their own breakneck efforts at Westernization." (p. 359)

"The Japanese were not comfortable with the rather different Western notion of seeking out the enemy without deception, to engage in bitter shock collision, one whose deadliness would prove decisive for the side with the greater firepower, discipline, and numbers." (p. 363)

"Although slow to anger, Western constitutional governments usually preferred wars of annihilation ... all part of a cultural tradition to end hostilities quickly, decisively, and utterly." (p. 364-5)

"In the final analysis, the root cause of Japan's defeat, not alone in the Battle of Midway but in the entire war, lies deep in the Japanese national character. There is an irrationality and impulsiveness about our people which results in actions that are haphazard and often contradictory. A tradition of provincialism makes us narrow-minded and dogmatic, reluctant to discard prejudices and slow to adopt even necessary improvements if they require a new concept. Indecisive and vacillating, we succomb readily to conceit, which in turn makes us disdainful of others. Opportunistic but lacking in a spirit of daring and independance, we are wont to place reliance on others and to truckle to superiors." (M. Fuchida and M. Okumiya, Midway, the Battle That Doomed Japan, 247). (p. 370)

Tet, January 31-April 6, 1968

Like the chapter on Cortes and the Aztecs, in which I learned some heavy statistics about the gory and bloody habits of the Aztecs, I learned about the brutality of the North Vietnamese. It seems that when it comes to Conquistadores and the US military in Vietnam, all we hear about are the brutalities of Cortes and the Marines. But when compared to the Aztecs and North Vietnamese, these sins seem to pale in comparison. The Western media was quick to point out Western mistakes and atrocities, but mute on the utter evil the Communists committed. The reasons behind this imbalanced view are complex, but the fact that this dissention even exists is wholly attributable to Western culture.

There are two passages that stood out to me. The first essentially discusses what went wrong in the war. The second sums up the role of dissent and self-critique, which was always on display, in the Viet Nam war.

"How odd that at the pinnacle of a lethal 2,500-year-old military tradition, American planners completely ignored the tenets of the entire Western military heritage. Cortes - also outnumbered, far from home, in a strange climate, faced with near insurrection among his own troops and threats of recall from home, fighting a fanatical enemy that gave no quarter, with fickle allies - at least knew that his own soldiers and the Spanish crown cared little how many actual bodies of the enemy he might count, but a great deal whether he took and held Tenochtitlan and so ended resistance with his army largely alive. Lord Chelmsford - likewise surrounded by criticism in and out of the army, under threat of dismissal, ignorant of the exact size, nature, and location of his enemy, suspicious of Boer colonialists, English idealists, and tribal allies - at least realized that until he overran Zululand, destroyed the nucleus of the royal kraals, and captured the king, the war would go on despite the thousands of Zulus who fell to his deadly Martini-Hentry rifles.

"American generals never fully grasped, or never successfully transmitted to the political leadership in Washington, that simple lesson: that the number of enemy killed meant little in and of itself if the land of South Vietnam was not secured and held and the antagonist North Vietnam not invaded, humiliated, or rendered impotent. Few, if any, of the top American brass resigned out of principle over the disastrous rules of engagement that ensured their brave soldiers would be killed without a real chance of decisive military victory. It was as if thousands of graduates from American's top military academies had not a clue about their own lethal heritage of the Western way of war." (p. 407)

"This strange propensity for self-critique, civilian audit, and popular criticism of military operations - itself part of the larger Western tradition of personal freedom, consensual government, and individualism - thus poses a paradox. The encouragement of open assessment and the acknowledgment of error within the military eventually bring forth superior planning and a more flexible response to adversity.

"At the same time, this freedom to distort can often hamper military operations of the moment." (p. 438)

Summary

I'm afraid I'm a victim to how Western media has continually criminalized the West for its wars and brutalities. There are two sides to every story. It seems as though all we hear is the one-sided, constant put-down by those who want to see the West destroyed. The way I see it is that if it were not for the West and its culture, the world would be a much more brutal place with much more death and destruction and injustice. Death and destruction and injustice will always exist among our imperfect human race. But that does not mean we simply let tyrants rule us or that we impugn those who seek to destroy tyranny. The West has consistently provided a culture which allows freedom to exist and flourish. Without that culture (and the military tradition to go with it), the world would indeed be ruled by tyrants and millions more would be slaves rather than free men.

Wednesday, October 21, 2009

Working

I've been diligent thus far this week ... at least with taking the SW during the day. The plan is to take 2 tbsp of ELOO when I get home from work at night, but I didn't drink it the last two nights.

Monday night was kind of bad. Although I didn't eat as much as before getting on the Shangri-la Diet, I still ate quite a bit. Last night was much better. I was still slightly hungry when I got home, but I decided to eat some tortilla chips with a cup of a bean-rice-corn stew my wife had made the other day. It was quite delicious, but I felt incredibly stuffed after eating it. After that, I drank two full glasses of water and was done for the night.

This morning I went on the usual jog. After I got home, I weighed in. Since we have an analog scale, it is really tough to tell what the exact reading is, but whatever it was, it was lower than I've ever seen it when I've stepped on that scale. To me, it looked like it was halfway between 205 and 210, so I called it 207.

Monday night was kind of bad. Although I didn't eat as much as before getting on the Shangri-la Diet, I still ate quite a bit. Last night was much better. I was still slightly hungry when I got home, but I decided to eat some tortilla chips with a cup of a bean-rice-corn stew my wife had made the other day. It was quite delicious, but I felt incredibly stuffed after eating it. After that, I drank two full glasses of water and was done for the night.

This morning I went on the usual jog. After I got home, I weighed in. Since we have an analog scale, it is really tough to tell what the exact reading is, but whatever it was, it was lower than I've ever seen it when I've stepped on that scale. To me, it looked like it was halfway between 205 and 210, so I called it 207.

Monday, October 19, 2009

Outrageous Quotes from the Book

Since I decided to go back on this diet, I pulled out the official Shangri-la Diet book authored by Seth Roberts. As I read the book, I had forgotton a lot of what he had talked about.

As I re-read parts of the book, I am shocked at his intial findings when he began experimenting with fructose.

Looking at his chart on page 28, it looks like he took about 10 tablespoons of fructose a day.

Here are two more outrageous quotes:

He was at 185 lbs when he started the fructose. He goes on to state,

Wow!

As I re-read parts of the book, I am shocked at his intial findings when he began experimenting with fructose.

The fructose water caused an astonishing loss of appetite. This was clear within hours. (I started with a dose that in retrospect was much larger than necessary. With a better, lower dose, it can take longer to notice the loss of appetite.) I ate much less than usual and lost weight fast. Fructose water suppressed my appetite much more than I expected. I halved my daily intake of fructose several times over the next few weeks, yet my appetite did not return. I continued to lose weight quickly, more than two pounds per week. (page 26)

Looking at his chart on page 28, it looks like he took about 10 tablespoons of fructose a day.

Here are two more outrageous quotes:

I ate about one meal every two days.

He was at 185 lbs when he started the fructose. He goes on to state,

I reached 150 pounds in three months.

Wow!

Saturday, October 17, 2009

Carinos and the Weight Scale

Friday is when my wife and I got out to dinner (usually). We wanted Italian so we figured Carinos would be good since we've not been there in about 10 years. I had sugar water in the morning (the usual ~3 tbsp). For lunch, I ate a Gala apple that had been sitting in my office the past few days.

After I got home from work, we went out. We ate the bread, the Italian sodas, the lasagne and everything else they dished us. Our conversation was almost entirely on the subject of the Shangri-la Diet. I told her that when she has some time to open Picasa and look at pictures of ourselves from back in 2006 and 2007 when we were both doing the diet. She had a lot of questions, but I talked her through them. I think she's on board. She decided to start on it Monday.

After dinner, we went shopping for groceries (how romantic huh). We got some ice cream. When we got home, we turned on the TV and watched The Office and ate ice cream. In other words, we ate a lot of food last night.

This morning was absolutly beautiful ... 60 degrees, clear blue sky. We went on a jog. Before I headed out the door, I hopped on the scale ... 210. I was pretty shocked because after all we ate, I expected to be over 210. We went on our jog and did about 4 miles. After the jog, I was just under 210, but I'm sure I would have been a little lower because I chugged a very large cup of water before I weighed in.

The only SLD I did today was drink a glass of sugar water. I've just snacked most of the day and have not felt hungry at all.

After I got home from work, we went out. We ate the bread, the Italian sodas, the lasagne and everything else they dished us. Our conversation was almost entirely on the subject of the Shangri-la Diet. I told her that when she has some time to open Picasa and look at pictures of ourselves from back in 2006 and 2007 when we were both doing the diet. She had a lot of questions, but I talked her through them. I think she's on board. She decided to start on it Monday.

After dinner, we went shopping for groceries (how romantic huh). We got some ice cream. When we got home, we turned on the TV and watched The Office and ate ice cream. In other words, we ate a lot of food last night.

This morning was absolutly beautiful ... 60 degrees, clear blue sky. We went on a jog. Before I headed out the door, I hopped on the scale ... 210. I was pretty shocked because after all we ate, I expected to be over 210. We went on our jog and did about 4 miles. After the jog, I was just under 210, but I'm sure I would have been a little lower because I chugged a very large cup of water before I weighed in.

The only SLD I did today was drink a glass of sugar water. I've just snacked most of the day and have not felt hungry at all.

Friday, October 16, 2009

Immediate Impact

After just two days back on the Shangri-la diet, I've seen serious results.

I drank about 3 tbsp of sugar water (rough measurement since I'm using the sugar dispenser at work) in the morning and another 3 tbsp in the afternoon right before I go home.

During the day, I am just not hungry. Of course I've been able to control myself during the day before Shangri-la, but I'd still be thinking about food. On Shangri-la, I'm not thinking as much about food. Yesterday, all I had to eat at work was a small Gala apple and a V8 (I figure I need to get vitamins some way).

The big challenge for me, however, is when I get home from work. I usually eat whatever my wife has cooked, or I'll scrounge for food in the fridge. The plan with Shangri-la is to drink 2 tbsp of ELOO with water as soon as I get home and then see how I feel in an hour.

So on the first day, I drank the ELOO and an hour later, I ate just half a sandwich and I was done.

Yesterday I did not drink the ELOO because my wife had made her famous chicken broccoli casserole. I ate a kid's bowl size of it (just over a cup). Afterward, I felt like I had just eaten Thanksgiving dinner. I drank a few glasses of water the rest of the evening and I was done.

This morning, I ran my normal 3.1 miles. It was perfect weather ... 68 degrees and low humidity. When I got back, I weighed in: 208 lbs!!

It has been over 4 months since I've been under 210 and I did everything I could to exercise and reduce my calories to get under 210. After four months of that, I'd still fluctuate between 215 and 210. And now after 2 days on Shangri-la, I'm below 210.

I drank about 3 tbsp of sugar water (rough measurement since I'm using the sugar dispenser at work) in the morning and another 3 tbsp in the afternoon right before I go home.

During the day, I am just not hungry. Of course I've been able to control myself during the day before Shangri-la, but I'd still be thinking about food. On Shangri-la, I'm not thinking as much about food. Yesterday, all I had to eat at work was a small Gala apple and a V8 (I figure I need to get vitamins some way).

The big challenge for me, however, is when I get home from work. I usually eat whatever my wife has cooked, or I'll scrounge for food in the fridge. The plan with Shangri-la is to drink 2 tbsp of ELOO with water as soon as I get home and then see how I feel in an hour.

So on the first day, I drank the ELOO and an hour later, I ate just half a sandwich and I was done.

Yesterday I did not drink the ELOO because my wife had made her famous chicken broccoli casserole. I ate a kid's bowl size of it (just over a cup). Afterward, I felt like I had just eaten Thanksgiving dinner. I drank a few glasses of water the rest of the evening and I was done.

This morning, I ran my normal 3.1 miles. It was perfect weather ... 68 degrees and low humidity. When I got back, I weighed in: 208 lbs!!

It has been over 4 months since I've been under 210 and I did everything I could to exercise and reduce my calories to get under 210. After four months of that, I'd still fluctuate between 215 and 210. And now after 2 days on Shangri-la, I'm below 210.

Thursday, October 15, 2009

Trying to Get Back on the Bandwagon

So I've been running 3 miles most mornings for the past 3 months and I've been trying to control what I eat. But no matter what, I'll occasionally binge eat. Then I'll feel guilty and then I get in my groove again.

Now the last three weeks, I've been quite religious about exercising and eating less. However, regardless of how little I eat and how much I work out, I cannot, for the life of me, break the 210 lbs barrier.

So I decided yesterday to pull out the old Shangri-la diet book and remember how it all worked. It occured to me that the last time I tried SLD back in May, it didn't work because I probably didn't take big enough doses.

I started yesterday and ended up taking about 3 tbsp of sugar with water twice ... once in the morning and once in the afternoon. And since my biggest weakness is eating at night when I get home from work, I took 2 tbsp ELOO with water as soon as I got home. About an hour later, I ate just half a sandwich.

In total for yesterday, I ate a banana, a granola bar, a small box of raisens and half a sandwich. Before I run in the morning, I usually weigh just over 210 and then after my run, I'm right at 210. This morning I did not run and I weighed exactly 210 ... so it seems there is a small victory right off the bat.

I'm actually determined this time to keep this up.

Now the last three weeks, I've been quite religious about exercising and eating less. However, regardless of how little I eat and how much I work out, I cannot, for the life of me, break the 210 lbs barrier.

So I decided yesterday to pull out the old Shangri-la diet book and remember how it all worked. It occured to me that the last time I tried SLD back in May, it didn't work because I probably didn't take big enough doses.

I started yesterday and ended up taking about 3 tbsp of sugar with water twice ... once in the morning and once in the afternoon. And since my biggest weakness is eating at night when I get home from work, I took 2 tbsp ELOO with water as soon as I got home. About an hour later, I ate just half a sandwich.

In total for yesterday, I ate a banana, a granola bar, a small box of raisens and half a sandwich. Before I run in the morning, I usually weigh just over 210 and then after my run, I'm right at 210. This morning I did not run and I weighed exactly 210 ... so it seems there is a small victory right off the bat.

I'm actually determined this time to keep this up.